Thoko Madonko from our Cape Town office speaks to Marlise Richter about inequity in access to covid vaccine in global south and gendered aspects of vaccine equity.

What are the main issues you want to raise about the rapidly changing pandemic panorama on equitable, accessible and affordable COVID-19 vaccines, drugs, therapeutics, and equipment and the South versus North imbalance in global trade, investment and financing?

Marlise Richter: The last two years have been overwhelming for probably everyone everywhere.

Most of us have lived with increased anxiety, uncertainty and a deep sense of sadness and loss for the many close to us – and those further away – who are scared, very ill, dying or who have succumbed to COVID-19.

If all lives were indeed deemed equal, it would have been impossible for some low to middle income countries to have just over 2% of their populations vaccinated

This state of grief and insecurity has encouraged us all to ask some much needed questions about the structural, social and political issues that have brought about and sustained the COVID-19 pandemic. Many have realised that these issues necessitate radical and urgent change and that we need to prioritise social and environmental justice more than ever. At the same time, others have used the pandemic to rake up extraordinary profits, exploit fear and to violate human rights. For example, Oxfam noted in September 2020 already how 32 of the world’s largest companies were likely to increase their profit by $109 billion for that year.

For me, the most burning issues relate to the concerns I raise above, namely the consolidation of capitalism; the ever widening gulf between the poor and the rich and between the Global South and the Global North; the environmental disregard that catalysed this pandemic[i]; and the lack of genuine global solidarity. If all lives were indeed deemed equal, it would have been impossible for some low to middle income countries to have just over 2% of their populations vaccinated at this point in time, while more than half of the population of high income countries have had at least one dose of a COVID-19 vaccine (see Diagram A)

What is the TRIPS agreement and why are its flexibilities not enough to counter the issue of fair and just access to vaccines worldwide? What do you have to say about the COVAX facility.

Marlise Richter: I have read KM Gopakumar’s (Gopa) excellent response to this question, and I have little to add aside from noting some more critiques of COVAX.

I believe people need to continue asking some tough questions about the COVAX initiative and to resist the argument that a TRIPS waiver is not necessary as COVAX “will provide”. As Dr Catherine Kyobutungi, Director of the African Population and Health Research Centre points out: “The way COVAX was packaged and branded, African countries thought it was going to be their saviour.”

Gopa has already said that COVAX’s (uninspiring) aim is to have 20 per cent vaccine coverage for low and middle income countries by the end of this year. It has already fallen behind on its own forecasts. The contracts and agreements forged through COVAX remain a secret and are not open to public scrutiny when a pandemic necessitates more transparency, not less. Most importantly, COVAX works within the paradigm of safeguarding patent rights, rather than insisting that COVID-19 vaccines are a global public good within a pandemic.

We cannot approach future pandemics in this way.

While South Africa and India were proposing a vaccine waiver, Pfizer and BioNTech were signing an agreement with The BioVac Insitute in Cape Town to produce mRNA COVID-19 vaccines for the African continent. Doesn’t this show that the TRIPS waiver isn’t really necessary to help create production in the Global South?

Marlise Richter: The Biovac Institute agreement was indeed celebrated and particularly so as it would mark the first company in Africa to help manufacture an mRNA vaccine. Of course, this is very necessary. The African continent imports 99% of all the vaccines it uses, not just for COVID-19. The continent –as well as countries across the Global South – has to build manufacturing capacity and increase their pandemic readiness. This requires political will, strategic vision and intensive investment – as well as the flexibilities that the TRIPS waiver would allow to deal with intellectual property barriers to scale up.

It is important to highlight that the agreement between the companies does not include a license for BioVac to actually manufacture the mRNA vaccine – all the active ingredients would still need to be imported from Europe. A key component of enhancing vaccine development is the transfer of technical knowledge. My colleague Fatima Hassan pointed out how the current arrangements foster dependence. She said:

“To expand global manufacturing capacity means that countries/ manufacturers must also have the freedom to produce the drug substance and to make their own production, supply and pricing decisions. We would all like to see the full terms of the agreement (of The Biovac Institute) and ask Pfizer why it can’t issue a full licence to multiple manufacturers. Why does it choose to play God – in a pandemic?”

How do you think gender plays out within the pandemic as a whole, and particularly concerning vaccine equity?

Marlise Richter: Medical anthropologist Paul Farmer and my former colleague from the AIDS Law Project and the Treatment Action Campaign, Mark Heywood, have written very eloquently about how diseases spread along the fault lines of inequality, and how ill-health in turn makes inequalities so much more severe.

Gender – as do race, class, nationality, etc. – plays a powerful part in the pandemic. For instance, it impacts on the measures available to keep oneself safe from COVID-19 infections – how one contracts the virus and how one might recover from it or be more serious. Gender also impacts one’s ability to access healthcare, the quality of services available to one, the amount of care work one has to do to keep others safe or cope with infection, the precarity of one’s livelihood and on whether one can access a vaccine or not.

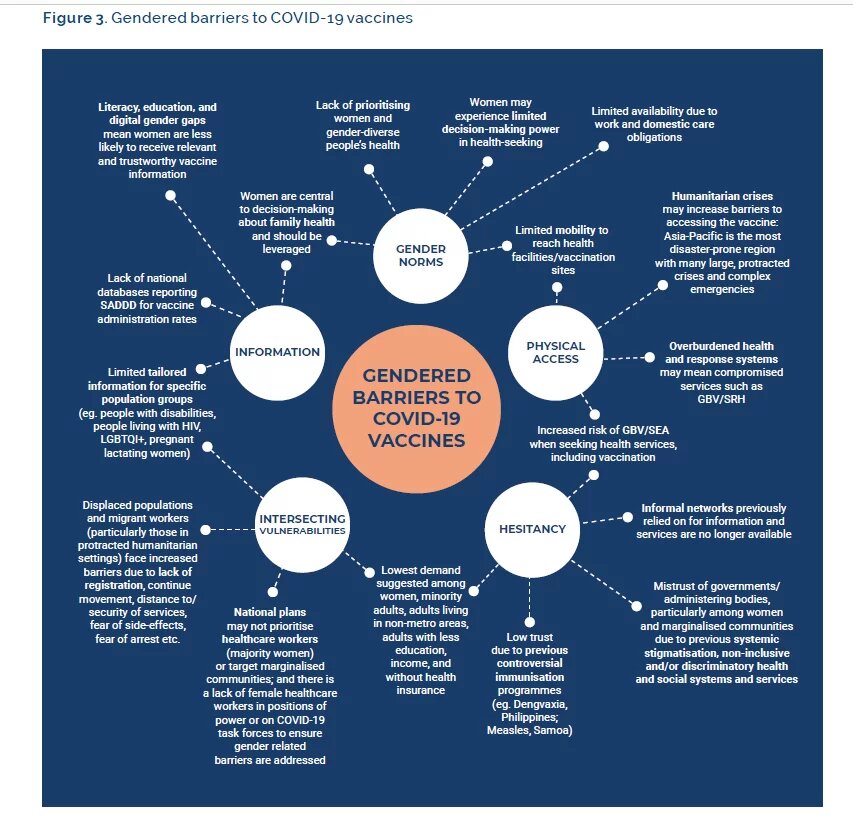

I like this diagram provided by the Asia-Pacific Gender in Humanitarian Action Working Group as it depicts some of these complex gender dynamics in relation to vaccine equity. It is situated within the context of Asia and the Pacific, but many of the points hold for other countries too – particularly in the Global South (see Diagram B).

I would like to include a concrete example from South Africa to illustrate some of the dynamics in the diagram.

I have worked in the field of sex work, health and human rights for close to 15 years, and am acutely aware of what a devastating impact the pandemic has had on the sex work context. Many sex workers’ livelihood strategies have been destroyed by the pandemic. Severe lockdown regulations mean fewer clients and thus fewer resources, while some of the law enforcement practices in South Africa have been absolutely brutal, and sex workers have been an easy target. We are still waiting for the outcome of an investigation into the mysterious death of Robyn Montsumi, a female sex worker who had been in custody at my local police station in April 2020.

Vaccine equity requires that everyone – no matter what their circumstances – has an opportunity to be vaccinated.

A number of sex workers have had poor experiences with healthcare services. Research has documented healthcare worker prejudice, discrimination and sexual moralism towards sex workers. I am concerned about how sex workers would access the COVID-19 vaccines and that they would need to do so from the same health system that has often alienated them. How would sex workers obtain good, evidence-based information about vaccines? Would they know how to register for the vaccine? Would they have mobile data to do so? Would they have sufficient transport money to get to the vaccination site, and also to make another trip later on if they are on a regimen that requires a second jab? Some sex workers are undocumented and it is currently not clear how South Africa’s vaccine registration system will deal with people without official documentation.

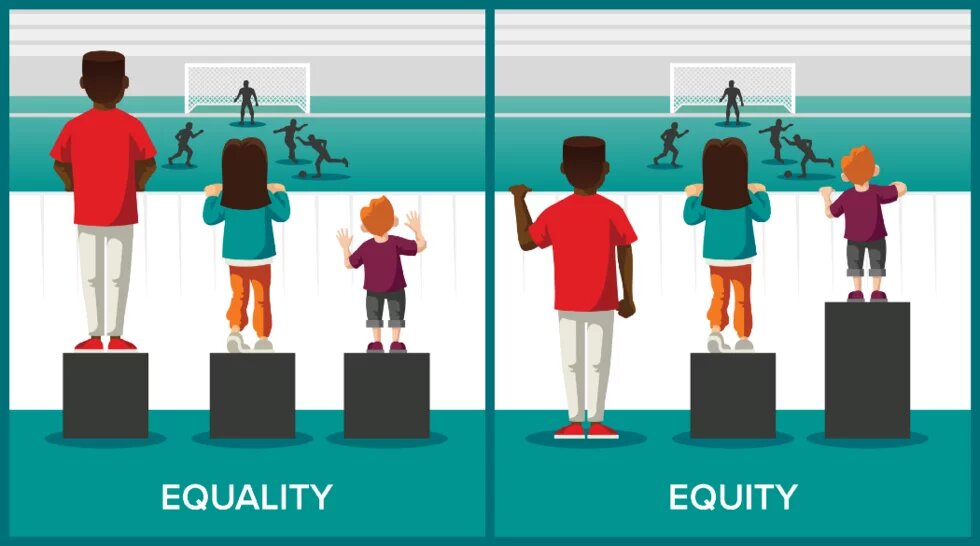

Vaccine equity requires that everyone – no matter what their circumstances – has an opportunity to be vaccinated. It reminds me of the picture explaining the difference between equity and equality in relation to a soccer match (see Diagram C below). True vaccine equity would practically mean that special strategies and resources must be directed towards the most marginalised and underserved populations to enable them to access vaccines, and for them to be safe. It requires that the health system understands the many diverse communities it serves, their material realities and the barriers that many face in seeking healthcare and to actively work to overcome these – much like providing boxes of different heights for the soccer spectators in Diagram C.

What are some of the other roadblocks to equitable global vaccine supply in addition to the patent waiver?

Marlise Richter : I am going to interpret “supply” broadly here and speak to factors beyond the actual chemical compound.

Some challenges to supplying vaccines to people include: How to transport the vaccines from manufacturers to the actual sites where they will be injected, keeping the vaccines at the correct temperature, having appropriate facilities where large numbers of people could be vaccinated without posing an infection risk as well as having sufficient and knowledgeable personnel to administer the services. The New York Times recently described it as the “difficulty getting doses from airport tarmacs into people’s arms”. It gives the example of how the US has donated 500 million Pfizer doses of vaccine through COVAX at a cost of around $3.5 billion. This amount is partly being funded by redirecting funds the US promised Global South countries to support their vaccine programme. The NYT notes that “Short on funding, those countries have had a hard time buying fuel to transport doses to clinics, training people to administer shots or persuading people to get them.”

Yet, with our actual vaccine rollout, the criteria of co-morbidities have strangely been dropped, and we are petitioning for the urgent inclusion of such.

I would like to add a South African example from the work of my organisation, the Health Justice Initiative. South Africa’s vaccine rollout was initially planned based on health equity, public health principles and international ethical guidelines such as those produced by the Strategic Advisory Group of Experts on Immunisation ( or ‘SAGE’, an entity that advises WHO). Our Department of Health’s original thinking was to prioritise healthcare workers and then work according to a system based on age brackets (the older you were the sooner you would get vaccinated) and co-morbidities. Yet, with our actual vaccine rollout, the criteria of co-morbidities have strangely been dropped, and we are petitioning for the urgent inclusion of such. Yet, ironically, the department recently announced a dispensation for “special groups” that includes amongst others, athletes representing South Africa and for those who require work or study related travel.

If South Africa’s unconditional commitment were to supply vaccines equitably, it would not have deviated from its original strategy in this way. Or it would have provided clear, evidence-based reasons for deviating.

COVID-19 has been a wake-up call for countries concerning their healthcare systems. How do we prepare for equally exceptional circumstances in the future, as certainly, this is not the last pandemic? What in your view would be the best/ most visionary way forward for addressing them?

Marlise Richter: I believe that the COVID-19 pandemic has not only shown us how absolutely critical it is to invest intensely in health but that the same should hold for social and environmental well-being. This requires a radical rethink of our national/ regional/ global priorities, the values we hold, who should lead us, and how we distribute power and resources.

“No-one is safe until everyone is safe”

A practical entry point might well be the current deliberations on a radical reconsideration of the Sustainable Development Goals and Agenda 2030, which could unlink the SDG targets from growth targets.

I believe that the popular pandemic slogan “No-one is safe until everyone is safe” is a valuable piece of wisdom that should be used to measure all our efforts towards global solidarity – whether in the midst of a devastating pandemic or not.

Endnotes

[i] My favourite billboard this year is from PETA and reads “Tofu never caused a pandemic. Try it today”.

This interview is part of series Democratising vaccine and its production -A perspective from India and South Africa . It is Jointly produced by Heinrich Böll Stiftung Capetown office & Heinrich Böll Stiftung Regional Office New Delhi.